Gemstone Trading on the Silk Road

Cody ManesShare

Gemstones Along the Ancient Trade Routes

The Silk Road, which stretched across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, was far more than a commercial corridor for textiles and spices; it served as a vital artery for gemstone trade that transformed economies, societies, and cultures. Along these routes, merchants carried highly sought-after materials such as lapis lazuli, jade, carnelian, garnet, and spinel. These stones crossed mountains, deserts, and river valleys, connecting kingdoms and empires through shared fascination with beauty, rarity, and wealth. Beyond the raw materials, traders shared knowledge about geological origins, stone-cutting practices, and valuation systems, which laid the foundation for the early development of gemology as both a craft and a science. Travelers and chroniclers, including Marco Polo, described gemstone caravans that supported economic stability and spread advanced lapidary techniques across continents. This globalized exchange transformed the Silk Road into one of the earliest frameworks of international gemstone commerce and permanently influenced the foundations of the global gem trade.

Gemstones were treasured for their rarity, toughness, and striking optical qualities. Rulers, nobles, and skilled artisans commissioned them for jewelry, decorative art, and insignia of power. Their inherent physical characteristics, such as hardness, resistance to abrasion, and ability to take a high polish, elevated them beyond ornamentation into symbols of permanence and prestige. Early merchants devised rudimentary grading systems based on color uniformity, weight, and transparency, anticipating principles that would later be formalized in modern gemology. Archaeological evidence of standardized weights used in Silk Road markets demonstrates an advanced understanding of gemstone valuation and quality control. These practices illustrate how ancient gem trading established intellectual and technical precedents that remain embedded in contemporary gemology and global gemstone industries.

The circulation of gemstones along the Silk Road also facilitated broader scientific and technological transfer. Methods of cutting, drilling, polishing, and classifying gems spread across borders, creating cross-cultural refinements in lapidary science. Traders and artisans regularly compared the physical attributes of stones such as fracture, cleavage, brilliance, and chromatic variation. These exchanges contributed to primitive systems of mineral classification that would later evolve into organized scientific methods. The dual transfer of both tangible gemstones and intangible knowledge ensured that advancements in lapidary practice became embedded in the intellectual tradition of gemology, shaping it as a discipline that continues to merge science and art.

Origins of the Silk Road and Early Gemstone Trade

The Silk Road emerged around the 2nd century BCE during the Han Dynasty, originally designed to support the flourishing silk trade. Over time, it expanded into a vast transcontinental network linking Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Gemstones quickly became among its most significant commodities. Caravans transported raw mineral specimens alongside finely cut and polished stones, evidence of the sophisticated lapidary traditions already present. Early merchants employed calibrated weights and elementary grading techniques, demonstrating an organized approach to gemological evaluation. The trade of gemstones thus satisfied luxury demand, stimulated intellectual curiosity, and contributed to early systems of natural classification.

The demand for gemstones was driven by the desires of royal patrons, the needs of artisans, and the interests of collectors. Stones sourced from Afghanistan, India, and Persia flowed into Chinese markets, where they were transformed into ceremonial artifacts, jewelry, and decorative objects. Archaeological discoveries of drilled carnelian beads, polished jade cabochons, and lapis inlays highlight the advanced lapidary skills practiced along the route. Written descriptions often accompanied stones, noting origin, weight, and distinguishing qualities, an early precursor to gemological documentation. The exchange of both raw materials and finished works stimulated intellectual progress in mineralogy and gemology, elevating the Silk Road beyond commerce into a crucible of scientific development.

The successful movement of gemstones relied heavily on nomadic tribes and caravan leaders skilled in navigating harsh terrains. These groups provided both logistical organization and military protection for valuable cargo. Historical records show that caravan leaders developed expertise in seasonal climate patterns, arranged defensive escorts against bandits, and utilized specialized pack animals such as camels for long-distance hauling. They also established caravanserais, rest stops that functioned as trade hubs where goods, ideas, and knowledge were exchanged. This infrastructure reflects the complex interplay between logistics, geography, and commerce in sustaining one of the earliest systems of international gemstone trade.

The Role of Central Asia in Gemstone Distribution

Central Asia formed the geographic and cultural heart of the Silk Road. Urban centers like Samarkand and Bukhara emerged as key nodes where gemstones from Afghanistan, India, and Sri Lanka were collected, processed, and redistributed across vast territories. These cities became cosmopolitan spaces where merchants, artisans, and scholars converged, blending commerce with technical innovation. Excavations of workshops reveal advanced drilling and polishing methods, as well as the earliest attempts at faceting transparent gems to maximize brilliance. Merchants from Persia, Byzantium, and China converged here to acquire rare stones and benefit from the expertise of highly skilled lapidaries. Central Asia exemplifies how geography, innovation, and trade created vibrant gemstone economies that reshaped gemological traditions.

The region’s location near Afghanistan’s lapis lazuli mines and India’s carnelian deposits positioned it as an indispensable distribution hub. In addition to lapis and carnelian, sapphires, garnets, and spinels circulated widely in Central Asian markets. Surviving written records suggest that merchants maintained logs of clarity, weight, and color saturation, forming an embryonic system of gemological record-keeping. These practices reveal the emergence of quality assurance and systematic evaluation in the ancient gem trade. By merging mineral wealth, geographic advantage, and craftsmanship, Central Asia developed one of the earliest sophisticated systems of gemstone commerce, laying a foundation for later global trade practices.

Beyond serving as a transit zone, Central Asia was a center of innovation in lapidary science. Historical accounts describe artisans experimenting with advanced polishing methods that accentuated internal color zoning in garnets and sapphires. Evidence suggests that faceting methods developed here influenced later European techniques for maximizing light performance. These achievements demonstrate that Central Asian workshops not only facilitated trade but also generated new knowledge, making them crucial contributors to the scientific and artistic evolution of gemology.

Lapis Lazuli: The Blue Gold of the Silk Road

Among the most celebrated gemstones traded along the Silk Road was lapis lazuli from the Badakhshan mines of Afghanistan. Distinguished by its vivid ultramarine hue and pyrite inclusions, lapis symbolized prestige and rarity across civilizations. Mesopotamian rulers wore it in jewelry, Egyptian pharaohs buried it in tombs, and European artists later ground it into pigment for masterpieces. Geological evidence confirms that the Badakhshan mines were exploited for over six thousand years, making them some of the oldest continuously active gemstone deposits on Earth. The mineralogical composition of lapis, comprising lazurite, calcite, and pyrite, produced unique optical properties that distinguished it from other blue stones. These features secured its place as both a cornerstone of ancient trade and a subject of early gemological inquiry.

For centuries, caravans carried lapis along arduous routes to distant courts and workshops. In Europe, it was transformed into ultramarine pigment, the most prized and costly color of the Renaissance, valued above gold for its brilliance and permanence. Venetian traders dominated its distribution, ensuring exclusivity and maintaining high prices. Scientific analysis of medieval artworks has confirmed Afghan lapis as the pigment source, proving its remarkable reach. The economic weight of lapis demonstrates how geological resources could exert influence over global art, science, and commerce.

The ubiquity of lapis across archaeological sites reveals not only high demand but also the organizational sophistication of Silk Road networks. From Mesopotamian beads to Renaissance paintings, lapis served as a physical and cultural bridge between civilizations. Modern gemologists study these artifacts to reconstruct early lapidary techniques, trade systems, and geological sourcing, positioning lapis lazuli as a case study in the intersection of gemology and international commerce.

Jade and Its Journey to China

Jade held unparalleled importance in Chinese culture long before the Silk Road, but the route greatly expanded access to high-quality nephrite. While domestic sources existed, jade from Khotan in Xinjiang became especially valued for its translucency and durability. Caravans carried both river-polished pebbles and quarried blocks to imperial workshops, where artisans carved them into ritual vessels, jewelry, and intricate decorative objects. Records describe the adoption of advanced carving techniques that emphasized jade’s optical and structural properties, setting standards that influenced later traditions of lapidary art. Geological studies confirm the abundance of jade in Khotan’s riverbeds, where centuries of natural erosion yielded nodules particularly suited for carving. This supply elevated jade’s prominence and contributed to early gemological appreciation for texture, polish, and geological origin.

The unique fibrous structure of jade gave it toughness exceeding that of most stones, enabling the production of thin-walled vessels, ceremonial blades, and delicate inlays. The ability to withstand breakage elevated jade’s significance as both a utilitarian and decorative material. These qualities ensured jade’s reputation not only as a cultural treasure but also as one of the most technically significant gemstones examined in early gemology. Its resistance to fracture and its polishability made it an exemplary subject for the study of material properties.

The jade trade reflects the interplay of geology, artistry, and commerce in shaping cultural identity. Historical texts describe jade transported in multiple forms, offering artisans flexibility in application. This availability spurred innovation in lapidary technology, including the introduction of abrasives and polishing wheels. Such developments improved precision and finish, enhancing both functional and aesthetic outcomes. Jade’s role in stimulating advancements in stone-working technology highlights its enduring influence on gemology and its central place in the history of global gemstone exchange.

Carnelian and Its Enduring Popularity

Carnelian, a red-orange chalcedony, became one of the most widely distributed gemstones along the Silk Road. The Gujarat region of western India was a major source, producing material of exceptional color and clarity. Workshops in this region pioneered heat treatment to enhance saturation, representing some of the earliest documented gemstone enhancement techniques. Carnelian’s durability and striking hue made it ideal for beads, seals, amulets, and intaglios, cementing its role in everyday adornment as well as elite contexts. Its ubiquity across regions reflects both its aesthetic appeal and its central importance to ancient gemological practice.

Archaeological evidence attests to carnelian’s distribution from South Asia to the Mediterranean. Standardized beads recovered from burial sites indicate organized production systems and a consistent market. Indus Valley workshops with specialized drilling tools highlight the sophistication of early lapidaries and suggest an industry devoted to mass production and quality control. These findings point to carnelian as a cornerstone of early gemstone industries and a major influence on the professionalization of lapidary work.

The global reach of carnelian underscores the efficiency of Silk Road networks. Beads with identical drilling techniques have been found in both Egyptian and Central Asian sites, suggesting interlinked or centralized production centers. Carnelian objects appear in urban marketplaces, trade hoards, and ceremonial burials, highlighting its role as both ornament and medium of exchange. For modern gemologists, the widespread presence of carnelian offers invaluable insight into early sourcing practices, enhancement methods, and trade systems that defined the Silk Road economy.

Garnet, Spinel, and the Stones of Power

Garnet and spinel were equally prominent in Silk Road trade. Garnets sourced from India and Sri Lanka were traded extensively, while spinel from the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan became famous as “Balas ruby.” These gemstones were incorporated into royal regalia, crowns, and high-value jewelry, their durability and vivid colors making them enduring symbols of authority. Geological studies confirm that Pamir spinels were exported widely and set into cabochons, adorning the regalia of sultans and European monarchs. Their prominence highlights the role of lapidary skill in creating objects of political and cultural significance.

Spinel was long confused with ruby due to their similar appearance, and many famous "rubies" in European crowns are in fact spinels. This gemological misidentification illustrates the challenges of classification prior to modern analytical tools. Garnets, available in greater abundance, circulated in bulk and were crafted into beads and small adornments that often served as currency substitutes. Their durability and wide color range enhanced their marketability and contributed to their central role in sustaining the gem trade.

The trade of garnet and spinel demonstrates the Silk Road’s contribution to mineralogical science. Their circulation across continents stimulated closer examination of crystal structure, refractive behavior, and inclusions. The confusion between ruby and spinel eventually prompted systematic classification efforts, laying essential groundwork for gem identification and mineralogy. Their global presence illustrates how gemstone exchange advanced both commerce and the science of gemology.

The Practical Value of Gemstones

Gemstones were not valued solely for aesthetic purposes; they were also studied for their intrinsic material properties. Hardness, durability, and workability influenced their suitability for tools, seals, jewelry, and pigments. Artisans observed fracture patterns, cleavage planes, and resistance to wear, making some of the earliest recorded empirical studies of mineral properties. These observations informed both lapidary practices and the selection criteria that remain central to modern gemology.

The movement of gemstones facilitated the transfer of technological knowledge. Carnelian’s capacity for engraving, jade’s resilience in tools and vessels, and lapis lazuli’s unique use as pigment demonstrate how practical applications intersected with gemological characteristics. Archaeological evidence reveals that artisans experimented with abrasives such as emery and quartz sand to refine surfaces and achieve precision in cutting. These practices contributed to the advancement of lapidary science, providing modern researchers with insight into early techniques of stone improvement.

The dual role of gemstones as objects of beauty and study emphasizes how trade shaped both artistic and scientific traditions. Excavated workshop remains show records of which abrasives worked best for particular minerals, suggesting comparative studies in early lapidary practice. Such experimentation demonstrates that Silk Road trade facilitated not only economic exchange but also the dissemination of empirical knowledge, laying the intellectual foundation for gemology as a systematic science.

Gemstone Markets of the Silk Road Cities

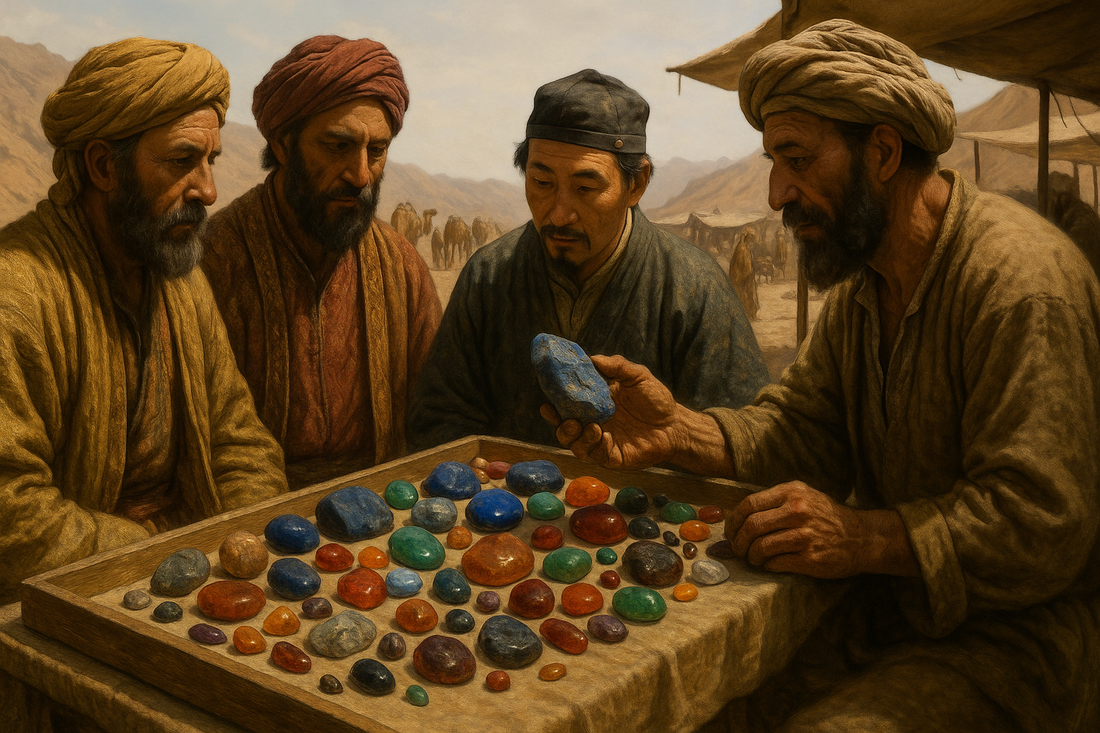

Urban centers along the Silk Road became thriving markets for gemstones, where commerce and education overlapped. Kashgar, Baghdad, and Samarkand hosted bustling bazaars where raw crystals were displayed alongside polished cabochons, enabling buyers to assess quality and provenance. Merchants used calibrated scales and reference stones, creating early systems of gemological assessment and appraisal. These bazaars attracted artisans, cutters, and jewelers, concentrating expertise and innovation in cosmopolitan settings.

Within these markets, gemstones were cut, faceted, and set into elaborate designs. Workshops experimented with new cutting angles and polishing abrasives to enhance brilliance and light performance. Traders documented these innovations and carried them across routes, spreading knowledge that influenced distant gem markets. This dynamic circulation elevated craftsmanship to new levels of technical precision and contributed to the globalization of gemological practice.

Markets also functioned as spaces of scholarly exchange. Merchants and travelers shared observations on geological sources, quality indicators, and lapidary techniques. Some of these observations were recorded, producing early texts that preserved and transmitted knowledge. Regional variations in terminology, grading, and cutting styles gradually converged into shared practices, further advancing gemology as a formal discipline.

Influence on European Jewelry and Art

By the Middle Ages, gemstones sourced through Silk Road channels had entered Europe, profoundly influencing both art and science. Lapis lazuli became indispensable as ultramarine pigment in illuminated manuscripts and Renaissance painting. Garnet and carnelian adorned reliquaries, rings, and crowns, demonstrating their continued symbolic and commercial significance. Treasury inventories from this period cataloged stones with increasing precision, noting color, weight, and provenance, an indication of growing awareness of systematic gem classification. The influx of gemstones into Europe encouraged experimentation in cutting, shaping, and polishing techniques that laid important groundwork for the later formalization of gemology.

European engagement with gemstones expanded beyond luxury and symbolism to include analytical study. Chronicles from courts and scholarly texts reveal attempts to categorize stones by clarity, brilliance, and geographic origin. This transition marked the shift from gems as passive objects of wealth to subjects of systematic study and scientific inquiry. The attention to gemological detail highlights how Silk Road exchanges shaped the intellectual as well as artistic traditions of Europe.

The integration of Silk Road gemstones into Europe illustrates the global nature of early gemological development. Exotic stones posed new challenges in cutting and classification, spurring innovations that influenced European standards for gem evaluation. The enduring legacy of these exchanges continues to shape jewelry design, mineralogical science, and the modern practice of gemology.

The Decline of the Silk Road

The dominance of the Silk Road began to wane with the rise of maritime trade during the Age of Exploration. Sea routes offered faster, safer passage, reducing reliance on overland caravans. However, the intellectual and commercial legacy of gemstone trade persisted long after caravans dwindled. Lapidary techniques, evaluation methods, and market structures cultivated along the Silk Road endured and adapted to new conditions. Records from this transitional era indicate that gemstone commerce shifted toward port cities, ensuring continuity in global trade.

Even as the overland routes weakened, centuries of accumulated knowledge survived. Innovations such as faceting, cabochon shaping, and gemstone grading were preserved in new markets and adapted with refinements. Many traditions of jewelry-making and gem evaluation trace their roots directly to Silk Road practices, demonstrating their resilience and enduring influence on global gemological expertise.

Although the Silk Road eventually declined, its impact on gemstone trade was foundational. Archaeological and textual evidence confirms that techniques developed along these networks informed later classification systems, valuation standards, and cutting practices. The intellectual and commercial ties established through Silk Road exchanges remain embedded in contemporary gemstone markets and continue to shape the trajectory of the industry.

The Silk Road’s Gemstone Legacy

The Silk Road was not merely a trade network; it was a conduit for cultural, commercial, and scientific exchange with gemstones at its core. Stones such as lapis lazuli, jade, carnelian, and garnet embodied both material and intellectual significance, linking distant civilizations. Archaeological finds reveal common lapidary practices and emerging classification methods, situating the Silk Road as central to the development of gemology.

The history of gemstone trading along these routes reflects humanity’s deep fascination with rarity, mineralogy, and craftsmanship. Gemstones served not only as luxury items but also as catalysts for systematic inquiry into mineral properties, cutting methods, and appraisal techniques. Evidence demonstrates that the gem trade fostered early classification systems, weight measurements, and valuation protocols that later formed the backbone of gemological science. Modern scholarship continues to draw upon these historical practices to trace the evolution of gemology and the structure of the international gemstone trade.

Today, the global gem and jewelry industries still echo the legacy of the Silk Road. Pricing models, grading standards, and sourcing strategies can be traced back to precedents set along these ancient routes. From international gem fairs to digital auctions, the gemstone industry continues to mirror the networks and traditions first established on the Silk Road, underscoring the enduring continuity of human fascination with the beauty and science of gemstones.